Hypnotherapy, hypnosis, hypnotism, hypnotic, Erickson, NLP, sceptical, stage hypnotist.

This essay was first published in 2009 as a three part series at

another web-site. It sets out to address the use of hypnotic "regression" and "recovered memory" techniques in investigation. However, it approaches the topic on the assumption that the reader begins with only popular-culture perception of hypnotism in mind. It is therefore a complete stand-alone introduction of the critical scrutiny of hypnotism with a final section relating to "regression" as used in UFO investigation, illustrating the detailed examination of particular issues in the study of the topic.

Hypnotism and the Illusion of “hypnosis”

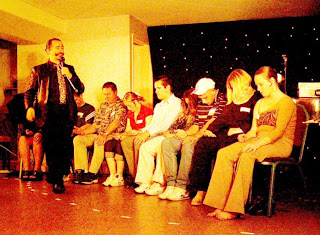

Fig 1. Stage Hypnotism.

-------------------------------

Few topics are of as broad and enduring fascination as that of hypnotism. There are few topics so widely and fundamentally misrepresented. There is virtually no other topic about which commonly accepted “expert” opinion, as it is represented in the popular media and expressed by practitioners, is so utterly and blatantly wrong!

That is a pretty strong assertion. But it is one that is so very easily substantiated. Let us just take a look at several examples of assertions widely made by “experts” on hypnotism and generally “accepted” as “fact” by both public and practitioners.

One of the most greatly respected British “authorities” on hypnotism in the latter Twentieth century was David “Dads” Waxman. Waxman was founder and president of the Medical and Dental Hypnosis [sic] section of the Royal Society of Medicine and eventually took over the editing of the “Bible” of British hypnotherapy, Hartland’s Guide to Clinical and Medical Hypnosis. In this capacity, Waxman repeated one of the great “chestnuts” of hypnotic mythology. That a person can be induced by hypnotic suggestion to become so profoundly deaf that a pistol can be fired near their ear and yield no reaction ( Waxman, 1989 ).

Leaving aside the idiocy of performing such a stunt ( the victims hearing would be wrecked whether they showed a reaction or not ) the rumour of this alleged “demonstration” has been repeated by various authors over many decades and none has ever provided a reference for its actual occurrence. It is apocryphal ( Van Pelt, 1958 ). But nor is that important. What is of crucial importance is that three decades before Waxman repeated this myth in the authoritative pages of Hartland’s, T.X.Barber had used a very simple experimental ploy to demonstrate that deafness supposedly induced by hypnotic suggestion is utterly fallacious.

This was reported in the paper “Experimental Study in Hypnotic Behaviour: Suggested Deafness Evaluated by Delayed Auditory Feedback”, British Journal of Psychology, 55. 1964. ( Barber and Calverley, 1964 ).

The study entailed subjecting volunteers who protested profound deafness and behaved consistent with that condition when it had been suggested, to “Delayed Auditory Feedback”. Simply put, ones own voice when fed-back via earphones at a moments delay renders most people incapable of normal speech. You may have experienced this when talking to someone via their mobile if the receiver picks up and relays your own voice back to you. A very disturbing phenomenon occurs which, personally, renders me incapable of continuing in more than fits and starts. It certainly rendered the supposedly “deaf” hypnotic subjects incapable of continuing to speak normally! Ergo, they were not in reality deaf, no matter how good a “show” they put on ( Barber and Calverley, 1964 ).

In fact, this experiment confirmed the findings presented by Sutcliffe in an earlier and now historically significant paper:

“Credulous and Sceptical Views of Hypnotic Phenonmena: Experiments in Ethesia, Hallucination and Delusion.” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 62. 1961. ( Sutcliffe, J.P. 1961 ).

Take another simple example. How tirelessly is it repeated by myriad “experts” that a hypnotic hallucination is as solid a “phenomenon” as seeing the real thing! Heavens… take away this precious assertion and you must begin to wonder what is left? Indeed, the truth , once apprehended, really should give one pause to wonder what in reality is left of the “phenomenon” of “hypnosis”. It was H.W.Underwood who in 1960 recognised a very simple test for the “veridicality” of this effect. He reported it in the paper “The Validity of Hypnotically Induced Visual Hallucinations” , Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 61, 1960.

When a person who is hypnotised and reports “seeing” a suggested image of lines converging upon a vanishing point and then “superimposes” this image upon a “target” of parallel horizontal lines, they should see the “Ponzo effect”. The parallels appear to bend. That is what we see when the lines are really there. Now, anyone who knows this can pretend that they see the parallels bend. But that does not explain the fact that those who pretend to see the converging lines superimposed upon the parallels do not report the bend! In fact, non-hypnotised subjects told to “imagine” the radial lines report the effect as often as those who have been hypnotised and report the positive hallucination! Only the subjects shown the real lines actually experience the illusion and report it consistently ( Underwood, 1960 ).

Now lets move on to the biggest whopper of them all. “Hypnosis” is a “state” of “relaxation”, right! Well, that’s what every “expert” from Dads Waxman to Paul McKenna tells us isn’t it? That’s what is tirelessly stated as a matter of fact by every “authority” wheeled onto television and radio isn’t it? That’s what all the guides to hypnotherapy arrayed on the heaving “alternative therapy” shelves of high street bookshops say, isn’t it? Well, whatever one else may believe, agree, or disagree about in the annals of hypnotic research, it is certainly a fact that “hypnosis” is definitely not inherently a “state” of relaxation!

In fact, numerous hypnotists themselves have professed as much for nigh-on a century. But lets not bring hearsay evidence into this. Let us not even cite the research of Ludwig and Lyle whose hypnotic induction method entailed having the subject pace up and down intensely whilst they shouted at them ( Ludwig and Lyle, 1964 ). No, let’s just jump to a really glamorous piece of research, conducted by no less a traditionalist and defender of most orthodox opinions on “hypnosis”, Ernest Hilgard. In was conducted conjunction with his colleague Eve Banyai and reported in the paper “A Comparison of Active Alert Hypnotic Induction with Traditional Relaxation Induction.” American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis. 19. 1976. In this study, Hilgard and Banyai famously demonstrated the practicality of hypnotising subjects who are not merely awake, but riding exercise cycles and becoming more alert as they “go under”! ( Banyai and Hilgard, 1976 ).

These are but three instances of two things. Firstly, what Barber called the “lore of hypnosis”, that is, the collection of beliefs and assertions that are passed on from writer to writer, generation to generation. Secondly, that a gigantic gap exists between that set of assertions and the actual facts as established when they are put to the test. Pretty much the same pattern applies to virtually everything that pundits have asserted over the years about the phenomenology of “hypnosis”. There is in fact, nothing, absolutely nothing, that can be done with “hypnosis” that cannot be done without. Which means that none of those “phenomena” constitute any kind of “evidence” for such a “state”. Indeed, the very notion of the existence of such a distinct phenomenon as “hypnosis” is bereft of support. But that does not mean that hypnotism is not a reality! Confused? Its simple really. Read on and I shall explain. I shall explain. In due course.

Clearly, there exists a distinction between bona-fide scientists, psychological researchers who are not professionally involved in the hypnotic industry and the vaunted scions of various professional bodies who represent those who are. Those who rely upon the widespread dissemination of blatant falsehoods in support of the claims and promises they make for their art. Hypnotherapists and “clinical” hypnotists. Such are the “experts” popularly endorsed by the media and publishers of self-help guides.

The Advent of a Scientific Study of Hypnotism.

Fig 2. Clark L. Hull.

Obviously, purveyors of snake-oil have been around since the very origins of hypnotism and Mesmerism before it. They have long had a knack for devising various “experiments” that are in fact stunts for the demonstration of the supposed “power” at their disposal. As Clark L.Hull pointed out ( Hull, 1933 ) these “experiments” were a travesty of scientific practice, lacking control conditions or any kind of baseline data. They “revealed” feats by hypnotic subjects that were in most cases later shown to be perfectly normal for non-hypnotised people. A classic example being the “experiment” by Heillig and Hoff ( Heillig and Hoff, 1925 ) which showed that when hypnotised subjects were told to “hallucinate” food, the contents of their stomach ( pumped out ) exhibited reactions consistent with the type of food suggested. Sounds phenomenal! But when the experiment was repeated properly ( that is, with control subjects ) it was found that exactly the same thing happens when the food is merely imagined by non-hypnotised people! Moreover, it gets worse…merely talking about food has the same effect. Even in the instance of one subject who was both blind and having no sense of smell! ( Hull, 1933 ).

It is worth noting that whilst myriad “phenomena” were attributed to hypnotic subjects ( “seers” or “mediums” ) over the rise of the Nineteenth Century, from time-travel to telepathy, as the era waned these claims fell away. What was left, the standard “lore of hypnosis” then came in for rigorous scientific scrutiny from the Nineteen Twenties onwards.

There had been antecedent stabs at a study. The French Royal commission of inquiry into the practice of Mesmerism under the tutelage of a number of scientists including Benjamin Franklyn conducted an informal experiment that demonstrated the status of “Animal Magnetism” to be that of a placebo, avant-la lettre. Whilst in England, Haygarth conducted a study of the alleged effect of Perkinean therapy ( an import from America every bit the rage in Britain that Mesmerism was in France ) which is now regarded as the first instance of a controlled double-blind clinical trial in history ( Haygarth, 1801 ). Then Paul Young conducted a brief study of hypnotic phenomena in the early Nineteen-Twenties before the grand master of scientific psychology Clark Hull took the stage.

Hull is known principally as one of the “fathers” of American Behaviourism. His ingenuity in experimental design and the rigour with which he articulated this discipline in practice was proportional to his scorn for the scientist-manques who had littered the field before him. Characters like Binet and Fere who thought it marvellous that a hypnotic subject could hold an arm rigid for a length of time that it was later discovered is absolutely normal in a non-hypnotised person. Hull made the acute and enduringly relevant observation that such “manky” pseudo-scientists were by and large clinicians. That medicine, strictly an art, is all to often confused with science not least by its practitioners, with the result that many arrogantly assert their dabblings as scientific when it is nothing of the kind ( Hull, 1933 ). Moreover, that such people enjoy an authority and status as scientists to which they are utterly unentitled. It is an observation of especial relevance in the present day. When anyone with a degree in medicine seems to think themselves entitled to make pronouncements on “hypnosis” as though it were their peculiar province although the topic is not covered in any orthodox medical curriculum ( Roet, 1986, p247 ).

Fig 3. The author with “Human Bridge” routine.

Much has been made of this. In fact, any fit person can do it. If they know that they can. The challenge for the hypnotist is, a) to get a complete stranger to do it and, b) without that person already knowing that they can indeed achieve this effect.

Fig 4. Another example from one of the authors informal bar sessions, circa 1993.:

Fig 5. The author has sometimes used two participants at a time:

Fig 6. In this instance the author has set up THREE participants as the Human Bridge.

Fig 7. In this case one participantt is more comfortable than the other.

Fig 8. In this publicity shot, the “volunteer” is actually a professional model:.

Hull established a team of researchers at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, later moved en-bloc to Yale. The studies recounted in his book “Hypnosis and Suggestibility: An Experimental approach” ( 1933 ) addressed many of the key “phenomena” of “hypnosis”. His work in the field was eventually stopped due to “complaints” from academicians, supported by…none other than the medical faculty, who in that instance attributed to hypnotism the status of an occult art!

The pattern which emerged from the work of Hull’s team had two aspects. Firstly, that many supposed hypnotic phenomena are without basis in fact. Secondly, with long term significance, that the phenomenon of suggestion is real, but occurs in both hypnotised and non-hypnotised subjects. Most evidently ( and objectively measurable ) in the effect of unintentional “ideomotor” movements induced by verbally engendering the expectation that they will occur.

It is one of the tragedies of the annals of hypnotism that Hull’s work was so brutally terminated upon the basis of that terrible union of ignorance and arrogance that he had himself warned against. Hull’s importance to research in hypnotism has largely been forgotten, supplanted by the absurdity of his being touted as the “teacher” of that arch deacon of credulity and principal latter day snake-oil merchant, Milton Erickson. Reading Erickson’s own version of events, it is quite clear that that particular medic and very definitely manky individual thought that it was he who had taught Hull ( “Conversations With Milton Erickson”, Vol 3, p151)! Or as one teacher put it to a friend of mine regarding their son, “You can’t teach anything to someone who knows everything.”

Realism versus Credulism.

Fig 9. Milton H. Erickson.

It was Milton Erickson who came to utterly dominate the field of hypnotism in-practice, in the Twentieth Century, which his career straddled like a colossus. Of course the most renowned dabbler in hypnotism in the Nineteenth Century, J.M.Charcot, had established his reputation upon the basis of very solid research in neurology, earning him the soubriquet “Napoleon of The Neurosese”. Erickson’s patently fantastical claims among a million words of books, papers and interviews almost entirely escaped critical examination ( the exceptions being in a colloquium featuring his friend A.M. Weitzenhoffer and part of one chapter in “Against Therapy” by Jeffrey Masson ) until I published “Beyond Erickson” in 2005. In the sub-title I chose to refer to him as “The Emperor of Hypnosis”. It was the translucence of his robes that I had in mind. Robes that in the minds of his generations of disciples were those of a veritable wizard. A preternatural “phenomenon” unto himself, able to hypnotize by a glance, to conjure hallucinations with a whisper, to distend time and warp space, to control people by his breathing! His accounts of such super-human feats actually sustain not the slightest credence. Some of the “papers” that he published in the magazine that he both founded and edited for the purpose ( The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis ) verge upon a travesty. His reasoning processes are feeble and subordinate to devious attempts at deception ( Tsander, a. 2005. p131-142, Erickson, 1965 ). He has no understanding of the principle of the control condition in experiments at all ( Tsander, A. 2005. p146. ) His conception of what constitutes “research” beggars belief: Typically, he published “papers” by his wife, relating a “study” conducted whilst out window-shopping one day in New York, twice ( Erickson, E.M. 1962, 1966, Tsander, A. 2005 p120 ) !

Nonetheless, Erickson was a man of great ingenuity and inventiveness. He single handedly invented or otherwise appropriated and promoted a huge range of highly innovative hypnotic techniques. If you wish to call him a “genius”, I would not demur, though I refrain from such ultra-quotidian epithets myself. Erickson, through his writing and decade upon decade of touring presentations forged a new vision of the practice of hypnotism as an adjunct to therapy if not a methodology unto itself. However, it becomes apparent upon close scrutiny of Erickson’s accounts of dozens of cases that hypnotism was a relatively minor, often indiscernible aspect of his “strategic therapy”. His techniques often amounted to hectoring, cajoling, bullying, arm-twisting, blackmailing and otherwise dog-cunningly tricking his patients into actions that would have a direct practical effect upon their circumstances and prospects.

The classic example of this is his “treating” a lesbian and a gay man, each of whom faced problems in their professional lives as a result of their clandestine inclinations, this being in a less than “open” era. Erickson saw the ultimate criterion of mental health as being married with children. Yet he also saw that the biggest problem facing these clients were their obvious lack of a partner rendering them suspect in the eyes of their employers. His “therapy” consisted of telling each of them that at a certain place and time they would bump into the solution to their problem and then arranging it so that they would literally walk into each other! They soon entered into a marriage of convenience. The “therapy” worked! What had “hypnosis” to do with it?

This brings us to the distinction that I raised earlier between “hypnotism” and “hypnosis”. “Back in the days” the former referred to the art or technique of inducing and manipulating the latter, a distinct condition or “state”. Distinct from either waking or sleep states. Akin to a neurological condition such as a temporal lobe epileptic seizure. But Erickson did something very cunning, much in keeping with the commercial, salesman-like way in which he created his “empire” of the hypnotic: he eradicated the distinction, using “hypnosis” to cover both sides of the equation and every other aspect of the field related to it.

The elision took, resulting in today’s absolute confusion in terminology. Every air-head on the block waffles on about “hypnosis” this and “hypnosis” that, whether they be referring to a technique, its putative effect, its application, the business it sustains or the lifestyle it may finance. I.e, “Paul McKenna is in hypnosis!”. As one person recently said to me “I’ve my house, my car, my truck and my boat and hypnosis paid for all of it, so it must work.” The result is a consequent woollying of any discussion of the field. Why would Eskimo’s have dozens of words for types of snow ? Because it permits of a refinement in the precision with which one can discuss the topic, so important to them. By the same token, if one cannot distinguish between the art, technique, practice, effect, manipulation, application or business of the hypnotic, how can one begin to order clearly ones thinking on the topic? For Erickson, this terminological ploy served to imprint hypnotism and hypnotherapy with a distinct new style that was specifically his. It may have been useful to him. But it has left us this heinous legacy.

Whilst Erickson’s status as grand Wizard of the West grew during the Nineteen Fifties, Sixties and Seventies, spawning new therapies from successive generations of disciples, Jay Haley, Ernest Rossi and then Bandler and Grinder, inventors of NLP, genuine scientific study of hypnotism continued in the wings.

By the Nineteen Eighties a vast body of data on hypnotic “phenonema” had been accumulated. None of it lent any credence to the now discredited belief in a distinct “state” of “hypnosis”. Many had sought the Holy Grail of evidence of such a thing. Many still do. More often, however, it is a case of pundits and the kind of hollow “experts” referred to earlier misinterpreting the more impressive seeming data obtained from research into the electro-physiology and vascular “economics” of the nervous system. The FMRI studies of Gruzelier and those of Benedetti are typical of work from which the brightly coloured data leave the mis-interpretors “blinded by science”. Such research indicates differences in the way “good” hypnotic subjects use their brain as opposed to “poor” ones, not the existence of a unique type of neural function induced by the actions of the hypnotist still less causing an experience. It’s a simple confusion easily clarified by comparison with music. A “good” pianists brain shows different patterns of activation whilst playing a piano than a non-musicians does when trying to do the same. It does not mean that playing the piano is caused by the “state” of activations that correlate with it! There is an even more pithy analogy. Suppose one tells the subject to lie when under the scanner. Asked “Is the moon made of green cheese?” they reply “Yes”. Compared to a non-lying condition their brains may well light up differently. Does that mean that this pattern, glibly dubbed a “state”, causes them to lie? Clearly, the proposition is preposterous!

This leads us to the orthodox view of hypnotic behaviour found in academic psychology. Sutcliffe, in the paper cited earlier ( ibid ) refers to the two “schools” or positions in relation to hypnotism outlined above as ““scepticism”. and credulism” ( although I prefer “realism” to “scepticism” ). T.X.Barber referred to a “New Paradigm” in thinking about hypnotism. This implying literally a “paradigm shift” in our conception of the topic in terms of Thomas Kuhn’s “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions” ( Kuhn, 1962 ). It originated with the concept of hypnotic behaviour being the product of the subject enacting “cognitive strategies”. “Strategic enactment”. Strategies of thought that generate a subjective version of events. The poor hypnotic subject, lacking the strategies, fails to imagine the “negative hallucination” that is my becoming invisible when I “suggest” it to them. They continue to see admit that they see me. The good subjects on the other hand effectively trick themselves into imagining that they cannot see me. They force me out of their awareness the way a school-kid does the miserable prospect of the impending academic year! The same goes for such things as amnesia. It is quite commonplace for someone to choose not to remember something. “Hypnosis” doesn’t come into it.

Such a way of thinking about hypnotic behaviour tied in with concurrent research revealing the plasticity of cognition and memory as well as the influence of social cues upon behaviour. Everybody now knows about Stanley Milgram’s experiments, in which manifestations of obedience were shocking, having nothing to do with “hypnosis” but being raw, pure, unadulterated. To a frightening degree ( Milgram, 1963 ).

Between these lines of consideration we find that everything hypnotic is ultimately accountable without ever needing to any longer adduce a special state of “hypnosis”. Just as notions of demonic possession used in primitive societies and by our ancestors to “explain” aberrant behaviour could be dropped with the advent of concepts of the unconscious and psychodynamics, so the “explanation” of hypnotic behaviour and interactions in terms of an unknown “state” of “hypnosis” becomes redundant in an age of social-psychology. There is nothing left for the concept of “hypnosis” to explain.

This brings up two fundamental misunderstandings about this “sceptical” as opposed to the “credulous” view of hypnotism ( Sutcliffe, 1961 ). Particularly in relation to the work of Barber and his colleagues, Chavez and Spanos. The use of control subjects who are not hypnotised but can produce the same effects as those who are, often provokes a response that Erickson himself raised in an interview: “Because it can be done without hypnosis does not mean it cannot also be done with hypnosis.” The whole point of such control replication of hypnotic “phenonema” by non-hypnotised subjects is that unless there is something that is peculiar to the alleged “state” and which therefore cannot be replicated, there is no reason even to raise the possibility that there might ALSO be another explanation, ie “hypnosis”.

Analogy: The suspect was with his wife when she was shot, had his fingerprints on the gun, had told the neighbours he was going to kill her, had powder burns on his hand and was found sat across the room from the body when the police arrived. But it could be that it was a purple dwarf wot-done-it, hypnotised the man, made him tell the neighbours he was going to kill her, put the gun in his hand and pulled the trigger, jumping out the window before the police arrived. After all, the window was open! Well, it could be that that explanation is true! But it is also fundamentally absurd to prefer it. It is what’s known as “Occams Law”.

The other misunderstanding of these “social psychological” explanations of hypnotic behaviour hinges on the words “role play”. Which is understandably interpreted by the general Joe but also by those who ought know better ( Waxman, et al ) as equivalent to saying “playing around” or “pretending”. In the context of social-psychology this most definitely is not what it means!

“Roles” are culturally engendered programs of behaviour that govern social interaction. A conception originating quite outside of research into hypnotism, in the area of social-psychology ( Goffman, E. 1959 ). When operating unconsciously as un-considered habits of behaviour and thereby unopposed they constitute a powerful set of tracks directing the conduct of every conventionally adjusted person in everyday life. In extremis, we see how such roles can be characterised by an aspect of intense compulsion, as indeed illustrated by that aforementioned famous work of Stanley Milgram. That study has been followed in the decades since by a large body of similar research. Some of it utterly eye-popping. Take Sheridan and King’s repeat of the Milgram study in which subjects were enjoined to give real electric shocks to visibly distressed puppy dogs ( Sheridan and King, 1972 )! Bickman’s study in which it was shown that merely appearing to be an authority figure empowered an individual to have members of the public ( who had no idea they were part of an experiment ) obey a command to give money to a complete stranger. Famously, again, Zimbardo’s U.S. Navy sponsored experiment revealing how volunteers fall easily into the “roles” of abuser and victim when “cast” in a guard and prisoner relationship ( Zimbardo, 1972 ). Research which, incidentally, leaves anyone familiar with it not in the least surprised by events at Abu Ghraib and speechless at the jaw-dropping naiivete of reporters who continue to wonder who “ordered” it. Such behaviour is a default condition under such circumstances. It need never be policy for it to occur in the absence of oversight by external authorities.

Social psychological processes do not only influence actions but perceptions and experience itself. Our cognitive processes are increasingly recognised as almost completely malleable and very, very unreliable. To put it very briefly, when we are not careful to use artificial methods to prevent it, we tend to see what we expect to see and that expectation tends also to be determined by our culture, society or context. This tendency reaching right into the fundamental processes of neuro-physiology, where traditional “feed-back / up” models are being supplanted by a conception of vision in particular that allows for “feed forward / down “ ( Churchland, Ramachandran and Sejnowski, 1994 ).

Against the background of such a broad and far-reaching field of research it becomes increasingly easy to understand the interaction between hypnotist and subject. The hypnotist employs methods, including the manipulation of expectation, context and subsequent recollection of the interaction, which engage multiple subtle aspects of normal behaviour. The good subject is one who is responsive to these influences and in response has what they recall as being a “hypnotic” experience. That including both the objective ( compliance with the hypnotists demands ) and the subjective ( belief that they could not resist, had really experienced ultra-normal effects, etc ). We need not expect the hypnotist to be aware of how his methodology engages social-psychological influences any more than any person need be aware of such things occurring every day, in their every interaction. All he needs is to repeat those conditions and actions that have been found to produce the desired response. It is like pointing out that sometimes kicking a faulty appliance in a certain spot makes it work properly. One does not need to know why! People who have not a clue how the internal combustion engine works can still drive a car! Meanwhile, the subject will be all the more responsive for not having such a critical awareness of what is taking place!

In fact, however, many if not all hypnotists, especially stage hypnotists, often implicitly acknowledge this reality in the way in which they go about “setting up” the subject. Indeed, many hypnotists explicitly acknowledge it. I have been publicly advocating such an acknowledgement on the part of all hypnotists since 1995 ( in The Stage and Television Today, second week of January ).

This brings us down to the basic distinction between “hypnotism” and “hypnosis”. Something I said I would explain, earlier. It is a critical matter of semantics upon which debate commonly founders. So you must ensure that you have a total grip on what I say in the next paragraph before going any further.

It is this: we need no longer waste our time looking for a supposed “state” of “hypnosis”. All hypnotic behaviour can be explained in terms of normal psychology. “Hypnosis” doesn’t exist. BUT, hypnotism, that body of techniques that has been found efficacious in inducing certain behaviour in an appropriate subject, most definitely works! As I have demonstrated with thousands of volunteers over the past two decades.

To be hypnotised then, is to fall under the influence of many subtle factors that, in truth, already affect us in every aspect of our existence as a social animal. What distinguishes the response of a simulating or “fake” subject from one who is “really hypnotised” is the fact that the latter, in contra-distinction to the former, interprets or experiences their response to ( they process and interpret their own sensations and actions induced by ) that methodology as being that of a special condition not of their own making or volition! To put that another way. “Hypnosis” is an illusion. “Hypnotism” is the methodology by which that illusion is created. It is analogous to the relationship between stage magic and the illusion of magical occurrences which it creates.

Implications.

The implications of the new perspective outlined above are many and far-reaching. They are perhaps most explicitly illustrated in the context of stage hypnotism.

The demonstration of hypnotism and, before it, the “Magnetism” of Mesmer et al, was from the very outset inextricably entangled with the process of “discovery” and “application” of these “phenomena”. This cannot be stressed too highly. Mesmer himself was a showman. His therapy practice was a theatrical undertaking. His successors and those who contradicted his views, paving the way for hypnotism as we know it, such as the Abbe Faria and Baron Du Potet de Sennevoy ( a fictional title ) actually gave regular performances in direct concurrence with their teaching and therapeutic work. Our own James Braid, to whom is attributed the very word “hypnotism” ( although in fact it had been in use fifty years earlier in France, ) actually lifted his techniques from observation of the French stage performer Charles La Fontaine.

Fig 10. J.M.Charcot, “Napoleon of the Neurosese”.

Numerous significant figures in the history of hypnotism in the Nineteenth Century whether a layman promoter of the art, a medical practitioner or a pioneer of some sort who was not also a performer either acquired their techniques from such performers or themselves gave “lectures” that were in fact stage shows under a spurious cloak of academic authority. The chief example being none other than that “Napoleon of the neuroses” Charcot himself, whose “lectures” at the Satpetrier hospital were luridly theatrical affairs, open to the general public and for a time a must-see event! Even Charles Dickens travelled to Paris for the specific purpose ( Thornton, 1976 ).

This duality continued into the Twentieth Century and is exemplified by, again, none other than that “Emperor of hypnosis”, Milton Erickson. A man who wrote scathingly of his disgust for stage hypnotism yet who built his reputation as a hypnotist upon the “demonstrations” that he staged throughout the U.S.A and Mexico. Reading his own accounts of such “lectures” it is apparent that they were nothing of the kind but, as a matter of fact, stage hypnotism masquerading as a pseudo-medical demonstration.

The importance of stage hypnotism in this history is that all the major alleged hypnotic phenomena ultimately derive from things “demonstrated” in a theatrical context. Whilst modern hypnotherapists take great pains to disassociate themselves from stage hypnotism ( although there are some who honestly conduct both practices ) the truth is that the entire fabric of their art and its continuing credibility in the mind of the public is almost solely the product of the illusions created on stage. A client in a hypnotherapy session is essentially required to yield very little by way of a dynamic response to the suggestions of the operator. The veracity of the major hypnotic “phenomena” is essentially untested in the hypnotherapists experience because the induction of such things does not arise in their practice. So they continue to believe in the reality of such things essentially on faith…because it is stated as so in the annals of their art, the “lore of hypnosis”. Moreover, that belief system is maintained by the continuing demonstration of the illusion of such phenomena in stage shows! Stage hypnotism could exist in the absence of hypnotherapy. The reverse is not at all certain.

Fig 11 et ibidem ( 11b to 11e ). The early Nineties.

So what really happens in stage hypnotism is utterly pivotal to an understanding of the true nature of hypnotic “phenomena”.

Let us leave aside those clowns who use stooges. I know of no examples and against the backdrop of my extensive experience it would seem to be a perilous practice to contemplate. Even though one uses entirely genuine volunteers who one honestly has never met before, the accusation that they include stooges is commonplace. To use such stooges would be to court suicide, or at least a severe kicking. How would one work several times a week, year in and year out, around the country but also repeatedly in the same places without either recruiting armies of these hypothetical stooges or having them recognised in their serial appearance! Certainly the Nineteenth Century practice of using regular subjects or “mediums” was liable to their being stooges. But the environment in which modern stage hypnotists work is so utterly different. The bottom line being, after paying the stooges, in addition to ones legitimate road crew and other expenses, how on Earth would it ever be profitable?

Fig 12. The author practising on strangers met in a bar, 1991.

So I think the stooge scenario is preposterous, for the public would see through it in a trice and it wouldn’t be profitable. However, I am also sure that some operators must have tried that avenue. Maybe one or two A&E wards have treated them after they had been “rumbled” by the punters! So let us assume stoogery may occur. Now let’s leave it out of the picture. An irrelevance.

Next take a look at some of the crude attempts made by Barber et al to “explain” stage hypnotism ( Barber et al, 1979 ). I wont go into detail, but they are an embarrassing addendum to the work of a man I admire and respect. Anyone who tried to use such obvious tricks as suggesting numbness in the arm of a volunteer whilst making him clutch a ball in his arm-pit ( interrupting blood flow ) would be subject to ridicule. Moreover, no audience would give a fig for such a routine as a man having his arm go numb. Crikey, what was Barber thinking? What audiences want to see are gross and very loud, very visual aberrations of normal conduct. At the very least their friends being attacked by imaginary ants and mosquitoes, talking Martian, ordering “Pigs Piss” from the bar, searching the audience for “stolen” parts of their anatomy, feigning sexual congress with toy animals, giving birth to others, etc, etc, etc. The kind of behaviour which I have been inducing complete strangers to engage in for the past two decades.

Fig13. One of the volunteers at a show searching for his stolen penis, mid nineties.

So how DO we explain this panoply of the “phenomenal” if not by adducing the actual “phenomenon” of “hypnosis”.

Again, let us leave aside those factors which would be utterly unreliable as a prop for such proceedings. You cannot expect to turn up at a pub where there might be …as sometimes happens… only ten people, and expect to reliably discover, time after time, several of them willing to do as you say simply out of a desire to make themselves the centre of attention. Such people do exist. But they are far from representative of the volunteering public in my experience. Not least because relatively few of the people that I select as volunteers want to take part in the first, sometimes second, or even third instance that I may ask them to do so!

Don’t even mention the influence of alcohol. It helps people to volunteer. It contributes nothing to their chances of being selected. The less intoxicated the volunteers are the better. This is not at all a controversial point.

Yet I maintain that there is no “state” of “hypnosis” at work. So how is the ability to induce such behaviour to be understood?

The clue is in the question. As a hypnotist I induce behaviour, not “hypnosis”.

The hypnotic induction indeed plays a part in this. But the mere fact of having successfully “induced hypnosis” is in most cases not sufficient to obtain from the subject anything by way of a substantive or even interesting response. The process has to be much broader than that. It entails manipulation of all influences upon the subject, from before we even meet them ( the information given in advance publicity ), to include the working environment, their friends, the audience, and a plethora of variables impingent upon proceedings from their initiation, through the hypnotic induction, and onwards beyond this.

There are two things that one learns from the close observation of a few thousand hypnotic sessions. Firstly, that the behaviour of subjects on close and sustained scrutiny is quite inconsistent with what one would expect were “hypnosis” to be an actual, bona-fide “state”. I devote an entire chapter to describing such observations in my book “Beyond Hypnosis: Hypnotism, Stage Hypnotism and The Myth of Hypnosis” ( Tsander, 2005b ) Secondly, that it remains nonetheless possible to create the impression that such a state exists in the mind of onlookers and subjects alike. At the very least to induce complete strangers to enact the entire panoply of hypnotic “phenomena” with no material incentive. A third observation, occasionally engendered in the odd instance of a sloppy performance ( everyone slips up in their work from time to time ) is that if one does not take care to govern all necessary variables in order to induce such behaviour, the mere hypnotic induction will of itself yield only a trivial response! The importance of this consideration is discussed again in my book “The Art & Secrets of Stage Hypnotism” ( Tsander, 2006 ).

In other words, the hypnotic induction is neither sufficient nor necessary to explain hypnotic behaviour as it is commonly induced in live demonstrations.

There are many insights to be gained from adopting this viewpoint. For a start, whilst it is a very big topic unto itself which I am not going to address here, it is worth glancing in passing at its relevance to that recurring theme of compulsion. This, surely, is at the heart of the general thinkers conception of what it is to be hypnotised: blind obedience.

Hynotists and their Delusions of “Power”.

In the Nineteenth Century there were scores, if not hundreds of legal cases hinging upon a nefarious individual compelling another to do their bidding by means of hypnotism ( Laurence and Perry, 1988 ). In most of these, there were very much more obvious explanations. Typically, it involved a sexual dalliance which, when uncovered, was claimed by a woman to be the result of the man having put a hypnotic spell on her. Interestingly, in most cases, she didn’t claim she was being so abused until the relationship was discovered by a third party, usually the husband or parents. The allegations involved such “phenomena” as being hypnotised by telepathy, mere eye-contact or enchanted notes and such like. The culprit was generally some lowly individual such as a gardener or stable-boy. Hypnotic ability used for a long time to be associated with the dog-cunning and sinister Earthiness of the “lower classes” and social “scum”. Look at George Du Mauriers “Trilby” and we find this in the disgustingly anti-Semitic but also class-inferior depiction of the character Svengali. But this feeling was not entirely without basis in truth. For dog-cunning is very largely about psychological manipulation and society’s “scum” are generally very adept at it. The hostility towards stage hypnotism exhibited by sections of the hypnotherapy lobby is very much framed in terms of an unconscious class prejudice. Irrespective of the actual social composition of stage hypnotism as a profession. Although I for one bill myself as a “Prole” and see no reason to apologise for the fact that my performances generally cater to “lower class” sensibilities, exhibited as they are by audiences of all classes!

Fig 14. The author “as” Svengali in the Victorian setting of the Llandoger Trow, Bristol.

Circa 1992.

Pause here to consider the two distinct phenomena that we need to address. One is that it is clearly possible to manipulate people. There is nothing controversial about that. It is part of life. Moreover that this manipulation can be formalised into techniques. Call them salesmanship, counselling or hypnotism, among others. The other phenomenon, quite distinct from such normal psychology is the alleged ability to control someone by means of the induction of a supposed “state” of “hypnosis”.

Criminal cases in which a hypnotic “power” is alleged or incidentally adduced continued throughout the twentieth Century and always offer a feast for the press. However, upon examination it invariably becomes apparent that hypnotism played no part in the actual crimes alleged or even proven to have occurred. A typical report of this type ( it is a genre unto itself ) from the present day involves a ( male ) hypnotherapist accused of molesting a ( female ) client. A terrible but very useful book “Open to Suggestion” by Robert Temple catalogues many such cases ( Temple, ). Typically, newspapers refer in lurid to a “hypnotist” abusing his “power”, to have his way with the victim. But reading on we find that his assaults involved no hypnotic procedure. The fact is that there is a long history of therapists physically molesting their clients. Inevitably, some of these are hypnotherapists. It is invariably a crude ( even fumbling ) assault and hypnotism plays little or no part in it. Then again, ask yourself, had it done so and were “hypnosis” such a powerful reality as is claimed, with efficacious amnesia, post-hypnotic suggestions etc, how on earth would such crimes be remembered by their victims?

In passing, I should mention a similar “thought experiment” regarding the “power” of hypnotism and stage hypnotists. They are only in it for money. If “hypnosis” were the bona-fide “state” characterised by awesome mind-warping potential as continues to be pretended, then any decent stage hypnotist, having established his “power” over innumerable bank managers, company managers, civil servants, estate agents, students destined for profitable and powerful careers in choice professions, among his volunteers over a few years, could retire a wealthy and powerful person in no great time at all! The reality, however, is quite plain and there to see. The most successful stage hypnotist in the UK in modern times, Peter Casson, continued working until his seventies, shortly before his death. Stage hypnotists in general do not retire at all. They do not earn enough to afford to!

In the Twentieth Century the attempt to demonstrate a bona-fide “power” of “hypnosis” was a continual saga. One of the most often cited figures in this connection being John “Jack” Watkins. Watkins worked for the U.S. Army, under the auspices of which he conducted a number of sensational “experiments” that are forever being cited by pundits as evidence of the “power” of “hypnosis”. Forcing classified rocketry secrets out of a secretary, making a soldier attempt to kill an officer under the delusion that it was a “dirty rotten Jap”. Actually succeeding in having a subject throw acid into the face of a technician. Marvellous. This being supposedly an “experiment” that went “wrong”. But I cannot help but think that Watkins was secretly pleased at the “result”. He was obsessed with the idea that he could compel others to do as he wished. This incident was perhaps his greatest, most often cited piece of supposed “evidence”!

It proved nothing. Watkins’ “experiments” take us right back a century to the kind of pseudo science which Clark Hull had castigated so scathingly ( Hull, 1933 ). Any bright school science student could point out that these stunts lacked the very most basic pre-requisite of a scientific experiment, a control condition. Most people who cite these pseudo-experiments as “evidence” for their faith in the “power” of “hypnosis” either do not know or choose to ignore the fact that when Watkins’ famous snake-handling stunt was repeated with non-hypnotised control subjects, they complied with the command to reach for the venomous reptile as often as those who did so supposedly “under” the “power” of “hypnosis”. Watkins’ work was trash!

The ultimate illustration of this kind of rubbish and of Watkins’ somewhat creepy obsession is found in his paper about supposedly forcing a subject to become hypnotised “against her will”. I emphasise that it was a female subject to give a sense of the kind of prurient and rather morbid flavour of the article. Many people cite it as “evidence” but few seem to have actually bothered to read it or they might be embarrassed to have mentioned it. The entire “study” consisted of the power-crazy professor going up to a nurse in a canteen, putting ( a miserable amount of ) money on the table and challenging her to stay “awake” in return for that “reward”, before launching into an unendurably tedious bunch of “you are getting very sleepy” malarkey. Reading between the lines of the “paper” it is obvious to anyone but a man who wishes to think that…as stated on the jackets of pulp guides…”the power of hypnotism can enable you to have any woman “ , that the tedium went on for about twelve minutes before the nurse realised the only thing that would shake off this nutter without causing a disciplinary hearing was to pretend to what he wanted!

As for Watkins’ other stunts, they do not either sustain sensible scrutiny. For a start, how would he have known that what the secretary “revealed” actually was classified information? Even if a third party who knew was asked, would he say “no” and have the crankey professor go on probing with the danger that something really would pop out? Wouldn’t it be safer just, like the nurse, to give the nutter what he wanted and say “yes”, its real data, “amazing professor, you’ve done it”. Whilst the episode with the “attack” on the officer bears an uncanny resemblance to the kind of scenes which I have hundreds of times observed in shows. Where the “assault” ( on, for example, the man who supposedly stole the volunteers’ million pounds lottery winnings ) may appear very real to the audience but on close observation ( and in video replay ) can be seen to be merely a pantomime of a genuine act of aggression. I hasten to add, such outbursts are not suggested by me, but sometimes arise out of the scenario, which I monitor closely, specifically for the very reason that these pseudo-actions can give the illusion of being real!

Fig 15. Men kissing women’s feet on post-hypnotic cue whenever the women shout “grovel”.

Fig 17...as above,

Fig 22. Note the incredulous man in a singlet….

Fig 24. Then in the street…weeks after first hypnotised

This is a kernel point. That it is possible in a non-theatrical context for a hypnotist to induce what is in effect a “performance” that in essence differs nought from the kind produced in a stage show. This can then be interpreted as a bona-fide effect whilst in reality it is a transient illusion. A classic example has been provided for us by Mr Paul McKenna. A while ago the performer made a play of demonstrating the supposed “power” of “hypnosis” to effect instant cures of phobia. On two different TV shows he took subjects with a phobia of dogs back stage and when they returned, lo, they showed no fear of the mutt brought on for the purpose.

The clue is again in the words I used. They showed no fear. That does not mean they were cured. It does not even mean they felt no anxiety. It means exactly what the words say: “They showed no fear”. It is easy to induce a subject to act as though they are afraid of something. It is easy to induce a subject to act as though they cannot see the hypnotist. It does not mean that in fact they are afraid of that object, or actually do not see the hypnotist ( as research outlined earlier confirms ). By the same token, it is going to be easy to induce a person to act as though they are “cured”. For the time that the “cure” is on display! It does not mean that this “cure” will continue off-stage. In effect, it does not mean that it is in any sense a cure whatsoever! It is merely an act. An illusion.

Worse than this arose when Mr McKenna tried to “cure” a woman’s fear of heights. They took the poor dear, supposedly now “cured” up in a cherry-picker to do a bungee jump. Even though this was edited footage, it was still mightily apparent that she was, in terms that the “punters” would favour, “cacking herself”. She was clearly terrified. McKenna and assistant simply kept on at her to do the jump until it was clear they were not letting her back down, literally. Again, like that nurse borne down upon by Watkins. She did it and we were then presented with this as “proof” of a cure. When in fact it was not even the illusion of a cure, but perhaps in the mind of Mr McKenna and crew.

Interestingly, Milton Erickson actually let slip that even in “real” therapeutic situations, the job of the hypnotist was to get the patient to act as though cured and to continue doing so long enough that they forget that they are only acting! A stunningly crisp and clear summation of these patterns of activity (*).

These are examples from “therapeutic” scenarios, but the same principle applies to attempts to demonstrate the “power” of “hypnosis” to effect compliance. When Watkins’ subject “attacked” his officer, I suspect that something of the same kind was occurring. It was, like the examples cited, an illusion which Watkins eagerly bought because he wanted it to be real.

In any case, the subsequent half century to Watkins’ famous stunts saw a plethora of carefully designed experiments on the capacity of “hypnosis” that makes an interesting contrast to concurrent work on the influence of normal social psychology upon behaviour. For, whereas non-hypnotised subjects were shown time and again to be liable to exhibit obedience in response to carefully created social situations, the reverse was found for “hypnosis”: that it proved quite incapable of producing compliance with even trivial “anti-social” tasks. For example, “hypnosis” was found quite incapable of inducing American college students to cut up the Bible or the flag of the United states! Indeed, in one cunningly devised study, female subjects were found less likely to respond favourably to a lesbian proposition when told they would do so “under hypnosis” than non-hypnotised control subjects! Crucially, these subjects were all approached by the experimental stooge and given a “pass” when away from the laboratory, in the “real” world, after they had concluded what had been presented to them as the actual experiment. Again, Milton Erickson had already long before this said in an interview that he and his colleagues had found that their wives had been found to be less willing to accede to sexual demands when sought via hypnosis!

Fig 25. One of the volunteers at a show becomes a “Chippendale”.

.

Fig 32. Three men and a woman with their friends outside a bar where they had met Alex Tsander one night in 1993.

Fig 33. Shows became more conservative

.Fig 35: Today the only mildly "racy" aspect of the authors' presentations are in his publicity materials!

Message to Magonia.

Finally,we come to the relevance of this debate to the topic of the UFO: the veridicality or otherwise of the alleged “phenomenon” of regression.

Quite clearly, this question lies at the very heart of many cases in the annals of UFO reportage, dependent as they are upon recovered memory and enhanced recollection. This being especially the case in regards the lore of alien abduction.

Memory is itself a troublesome topic about which there are many outdated notions and popular myths. Key among these being that memory is the manifestation of the brain acting as a kind of tape-recorder. Pause for a moment and wonder whether that idea could have been currency before the invention of the tape-recorder? Before the advent of photography? What then, was memory a kind of illuminated script? In fact, this is perhaps a better analogy than that of a tape recording.

Enough evidence now exists for us to reliably agree that whatever it is, memory is not reliable. It is plastic, malleable, subject to alteration, reinterpretation and corruption. In fact, enough evidence now exists that the notion of people being legitimately convicted of crimes on the basis of “eye-witness” testimony is coming to seem very questionable. Most readers will be aware of how hypnotic memory recovery procedures can accidentally result in false recollections. But it is also the case that this can happen where no hypnotic procedure is employed.

So the notion of a process whereby the “tape recording” of memory can be “re-wound and replayed” is very dubious. We need to consider this in some detail. I am going to “cheat” by simply pasting in a passage from my aforementioned book “Beyond Erickson”. I have made only a few modifications and one addition.

------------------------------------------------------Quote:---------------------------------------------------

Along with hypnotic anaesthesia and hallucination, regression is one of the central elements of the "lore of hypnosis". The idea that a hypnotised person can be "taken back" to an earlier time in their experience like a tape-recording being re-wound has entered into the popular imagination and appears frequently throughout our culture, not merely in the claims of hypnotists but in films, plays and books where it sometimes forms a key to plot and in which its reality is never questioned. The supposedly “authoritative” Hartland’s reference text, under the editorship of David Waxman credulously asserts the following:

“Sometimes the revised memories of the regressed subject can be checked. It has been reported that when an adult subject, regressed to her seventh birthday, was asked what day of the week it was, she replied ‘Friday’ without the slightest hesitation and subsequent investigation proved this to be true. This is a feat of memory that few of us could achieve in the waking state.” ( Hartland’s, Waxman, ed’. 1989, p180 ).

How misleading this passage is will become apparent when we review the research on this supposed feat. Meanwhile, Harry Aaron’s described the idea in the following terms:

“Scientific research has demonstrated that the mind - or the brain - seems to have the capacity for retaining all impressions which enter it, like a giant tape recorder” ( Aarons, 1967 ).

Of course, “Scientific research” has shown nothing of the kind. Although someone like Aaron’s might enthusiastically leap to this conclusion on the basis of an interpretation of the work of Wilder Penfield. Penfield, a Canadian neuro-surgeon, performed over a thousand pioneering operations to cure some types of epilepsy. In these operations, the patient was conscious, having been given local anaesthetic to the scalp, cranium and sub-cranial tissue. The skull was opened up but, as noted earlier [ in Beyond Erickson ] and is indeed well illustrated by this practice, the brain yielded no sensation, let alone pain. In order to locate the specific place at which to work Penfield electrically stimulated selected sites on the cortex of the patients brain. The patient could report what they experienced in response. Sometimes sounds. Sometimes sights. Sometimes other sensations. Combinations of these things or all of them at once. In effect, resembling momentary flash-backs in time. The reporting and popular re-reporting of such events as a patient remarking that she could hear a piano being played in an adjoining room ( at home, in the past ) when a certain spot was stimulated no doubt did much to help fuel the notion that the brain records everything, electrically, like a tape-recorder. Indeed, that most credulous “authority” on “hypnosis”, David Waxman ingenuously asserts:

“It was said of these experiments that the recall is total and equal to that which can be achieved with patients under hypnosis.” ( Waxman, 1981, p42 ).

Thereby arrogantly implying that the reality and power of “regression” under “hypnosis” was actually more certain than the physical effects of an electrode stimulating the brain!

However, as Stephen Rose, in his book the “The Making of Memory”,( Rose, 1992 ) remarks:

“...there is the problem of deciding whether what is being elicited by such stimulation is a ‘real’ memory for some event which has actually occurred, or, like a dream or hallucination, some type of confabulation. The very nature of the records means that one can never be sure about this; the Penfield studies remain fascinating, challenging, but ultimately uninterpretable.” ( Rose, 1992. P 130 ).

Even in “Hartland’s”, edited by Waxman we find the concession that:

“It is a fallacy to believe that every event or experience, however trivial, is somehow registered in the mind, never to be forgotten.” ( Hartland, 1989, p467 )

Nonetheless, a great many writers and “experts” continue to maintain exactly that. Harry Aarons was very far from unusual in holding ideas such as those expressed in the earlier quote. Indeed, it remains common-place for therapists to sell the notion that everything we ever experience is recorded comprehensively and with absolute veracity somewhere in our head. Even a close friend of mine who was at the time lecturer in biology at a leading medical school, in her ex-curricula capacity as a private therapist expressed exactly this dogma. Moreover, the naive conception of memory as a kind of tape recording, which can be rewound in "regression" has been extrapolated to ever more absurd extremes. Weitzenhoffer ( 1989 ) points out how absurd it is for supposedly intelligent professional people to treat seriously the claim that it is possible through this procedure to recover memory of intra‑uterine experience which would not in fact have been subject to processes of memory formation in the first place. But many who consider themselves "hypno-therapists" go further, and it is not unusual to see in the press or on television, hypnotists billed as "hypno-therapists" claiming an ability to routinely regress clients to earlier incarnations. Indeed, as a hypnotist doing stage-shows I have found that the number of individuals asking off-stage if I can stop them smoking are almost matched by those asking “Can you do regression”. Invariably, I discover that by this they mean regression to a former life!

There is a need here to distinguish between various “strengths” of alleged regression phenomena. At the “strongest” we have the meta-physical “past-life” regression. This is championed as a literal reality and an actual therapeutic tool by a former recovered-memory therapist, B.L.Weiss, in “Through Time Into Healing” ( Weiss, 1992 ). Then there is the “major” version of present-life regression that is based on the idea that all experience is remembered and that this “recording” can be re-played, re-entered, “zoomed” into, “enhanced” etc, exactly as if it were a video. Undoubtedly championed by, among many others, the advocate of forensic hypnotism, Martin Reiser ( Reiser, M. 1980; Ofshe and Watters, 1995, p37 ). Then we have the “minor” version of regression, which accesses repressed material or inhibited recall by giving the patient licence to report it as though really replayed. In which the reality or otherwise of the effect is not relevant to its utility in accessing and ventilating that material. As illustrated by William Sargent in his accounts of treating battle survivors during WWII ( Sargent, 1957, 1974 ). Then there is an entirely “soft” version of regression which is really not even assumed to be a hypnotic reality but is a method of aiding recall and accessing memory. Such that it may not even be referred to or presented as a “regression” whilst undoubtedly on this same continuum. Into this camp we can put the vast swathe of “recovered memory” “therapy”. Illustrated by Bass and Davis ( “The Courage To Heal”, 1988 ). A field thoroughly examined in its full diabolical implications in “Making Monsters, False Memories, Psychotherapy and Sexual Hysteria” by Ofshe and Watters ( Ofshe and Watters, 1995 ). Into this category we can also place a “Pure pseudo-regression”, in which it is not even considered important whether the visualised information is a memory or just something immediately imagined, described by one “therapist”, Renee Fredrickson, in these extraordinarily shameless terms: “Whether what is remembered around the focal point is made up or real is of no concern...” ( Fredrickson, 1992 ). Then, beyond this, at the extreme, we have a “Pretense pseudo-regression” that is not even a memory strategy but is openly an act, as has been in the past used in demonstrations. In other words, the routine of acting as-though of a certain age.

Clearly, what we are concerned with here are the “strongest” and “major” versions of the alleged phenomenon. The “minor”, “soft” and “purely pseudo” versions do not entail the necessary reality of a substantive and questionable phenomenon. They do, however, have very serious implications for both those engaged in such processes of recollection and those who the supposedly “recovered” memories involve.

Even without the supernatural or metaphysical dimension of “past-lives” the claims associated with regression are such that they indicate a failure on the part of those who make them to grasp the enormous implications of what it would mean. Moreover, although claims for the veracity of regression are largely accepted by an uncritical public, experimental support for this belief would be remarkable and is as yet unforthcoming.

It would be especially remarkable in consideration of it contradicting everything that is today known about memory. Although at one time it was indeed contended by some speculative psychologists that every experience is recorded for perpetuity, this is now realised not to be the case. The brain contains a vast number of pathways and potential for the registering of “N-Grams”. The brain, as everyone knows, is the most complex known structure in the universe. But knowledge from computing tells us that the information storage capacity required to register even one second in any one of our senses is such that even that vast potential would be used up long before we reached adulthood. This cosmologically immense data encoding and storage requirement would necessitate a truly “astronomical” tape-recorder indeed. The only way that the idea of every sensation in every moment being recorded could be realised is if our brains were in some way connected to a virtually unlimited storage capacity in another dimension. A kind of neo-dualism!

At the start of the Twenty-First Century, one can obtain a visceral sense of this problem through our infuriating practical experience of the limitations on digital information storage, transfer and retrieval. Use digital photography, let alone video, transmit the images over the internet, via optical relays, let alone a mobile phone and we find immediately how even some of our most powerful systems are capable of handling only a tiny sliver, not even a whole stream of the information we experience. This effect will gradually disappear. As processing speeds, bandwidth and memory capacities increase, our experience of information processing will lose the visceral sense of struggling to cope with the sheer Volume of data in a picture, a sound, a moment, that at the start of the Twenty-First Century it is still characterised by. Indeed, compare file sizes for a book and a photograph and you can establish for yourself that a picture certainly paints vastly more than a thousand words! Although our technology is expanding to ever more immense storage and transmission rates, today even the most powerful super-computers perform equivalent to only a tiny proportion of the work required of a human nervous system to process a single second of consciousness. Even the most extensive computer memory could not handle as much information as is stored in a few minutes of human vision. Immensely more subtle than any camera yet devised. Multiply these ratios to match the data processing and storage capacity requirements of a lifetime and we would also many times exceed the even astronomical scale of capacities of the human brain. The only way it can manage to complete this lifetime of information-processing is by expending relatively little on memory, re-using cycles of activation and consuming resources conservatively.

To do otherwise would be like trying to keep every digital photo we ever take, deleting none, on the memory card the camera came with. It would soon be full to capacity. We are obliged to delete images and re-use the space. The analogy is not precise, but is indicative of the economic principle.

One researcher who has devoted a career to studying the biochemical basis of memory put it like this:

“I have already made the point in connection with the filtering process of short-term memory. Information stored in such a memory need not be transferred to a more long-term store - and indeed there is a biological necessity that much of it must be filtered out if we are not to collapse with memory overload.” ( Rose, 1992. P320 ).

The reality of human memory is that it is less like a tape-recorder and more like a tradition in a culture. A certain ritual may be passed on from generation to generation. A cultural memory. If the process is not repeated the link is lost. Any society can only devote a finite amount of resources to sustaining the most important cultural memories or traditions in this way.

Each memory is to an extent a record of the last time that it was recalled. Just as each generation of Morris Dancers repeats what it was taught by the last. Although we may wish they wouldn’t! It is an active and dynamic process in which the limited resources available mean that only a tiny amount of the sensory information associated with only a small number of temporal junctures is retained and passed on in this way. It is possible to break the chain or improve the link, alter or insert new ones entirely. As Stephen Rose again puts it:

“Obsessed with the attempt to see how far back in my childhood I can remember, I have taken out these internally filed photographs, redeveloped and reprinted them, cropped them a little differently, made them matt or gloss, black-and-white or colour, enlarged them to fit a new frame just as much as Bergman has transformed his for public viewing. Every time I remember these events, I recreate a memory anew...” ( Rose, 1992. P35 ).

The fact is that it would be impossible to “replay” with any accurate detail what happened in a single mundane one of your “yesterday’s” let alone “re-wind” to an event in the remote past and not only “replay” but “zoom-into” and “pan-around” as has often been claimed ( Reiser, M. 1980 ).

I am reluctant to adduce a-priori arguments against the possibility of something, but in this connection there are a couple more which are so obvious that they cannot be resisted.

For a start, human vision is highly “hierarchical”. That is to say, at the centre of our optical field is a tiny point of focus and everything around that is progressively less focussed outwards from that centre. We perceive the world in terms of a focussed image because our eyes are continually scanning and our brain synthesises a representation from the data thus gathered. However, we do not scan, focus upon or examine every aspect or possible point of focus in our visual environment. To do so would take an infinite amount of time, because the subject under scrutiny would have changed before the task could be completed. These things considered, it is quite obvious that anyone “really” “regressed” to a particular time and place would nonetheless still be unable to focus upon, let alone examine every aspect of their experience of that occasion at will. They could only access the same material as would have been stored as regular memory traces. If all we mean by “regression” is therefore enhanced access to such conventional memory traces the core defining aspect of the alleged “strong” or “major” versions of “regression” are passed over in concession to something “minor” or “soft”.

Considering the above also should give one pause to consider the fact that our perception of the world and our experience in time is a construct of our nervous system, integrating various sensory inputs according to diverse biological parameters and prior experiences. We do not store the original inputs. This can be illustrated by analogy to digital photography once again. Some cameras have a RAW facility which records the original data as it arrived in the processor from the imaging sensor, before processing. We can take this RAW data to our computer and then adjust it according to our desired interpretation to produce a finished image file, a JPEG. However, from this JPEG it is not possible to reconstruct the image in others of the many thousands of possible alternative forms from which it could have been constructed using the data in the original RAW file. Although it can still be slightly altered it is relatively fixed. This is one reason why professionals typically prefer a camera that produces a RAW file to one that immediately makes one of the possible versions of the image from that data and stores it solely as a JPEG. ( Another reason is that of avoiding compression, which is not relevant here ). By analogy, the human nervous system is one of the latter variety of devices, lacking a RAW storage capacity. It stores as “memories” the processed cognition, analogous to the JPEG. Without the existence of the analogue of a RAW file, comprising the unprocessed sensory data, it is impossible to “zoom”, “pan” and “enhance” even if “regression” were “real”.

All this leaves is the possibility of enhanced recall, which is a lot less than the proponents of “regression” try to sell us. Strictly described as “hyperemnesia”, this is discussed further, below. Suffice for the moment to mention the dominant question thereat being not whether psychological techniques can enhance recall, which is not disputed, but whether “hypnosis” contributes anything to such techniques that would constitute evidence for its “reality”.

Experimental demonstration of the phenomenon of the “strong” or “major” versions of “regression” would require a complete re-think of the relationships of consciousness, memory and our connection to the physical universe. Nonetheless, attempts have been made to obtain such evidence. In 1949, R.M.True published a report of a study in which subjects were regressed to the ages of 11, 7 and 4 years and correctly named the day of the week in which their birthday and Christmas day occurred. Barber points out that it is possible for a determined subject to calculate this and, more importantly, that the method employed by True of eliciting the date via a yes or no arrangement ( in which the experimenter asked, "...is it Wednesday, ...is it Thursday,...is it Friday..." and so on ) allows the subject to discern cues for the appropriate day unwittingly given by the questioner in their tone of voice. However, the damning verdict on the study is that numerous researchers have attempted to replicate the positive findings and obtained only a negative, contradictory, outcome. Including:

“Living Out “Future” Experience Under Hypnosis”.

By Best, H.L and Michaels, R.M.

In Science ( 1954, Issue 120, p1027 )

“Experimental Evidence for a Theory of Hypnotic Behavior: 2: Experimental Controls in Age-Regression.”

By T.X.Barber

in The International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis ( 1961, Vol' 9, pp181-193 b ).

“Problems of Interpretation and Controls in Hypnotic Research.” By Fisher, S.

In Hypnosis: Current Problems. ( 1962, Ed G.Estabrooks, Harper New York ).

“An Investigation of Hypnotic Age-Regression”

By Leonard, J.R.

Doctoral Dissertation, University of Kentucky ( 1963 ).